The Guerrilla Feminist is reader-supported! Thank you to the folks who pay monthly to support my work. If you want to upgrade to paid, go here.

Add your favorite song to The Guerrilla Feminist Spotify Playlist!

Please share my writing with your community and comrades! Forward this email to a friend, put it in your own newsletter, screenshot and share it on social media.

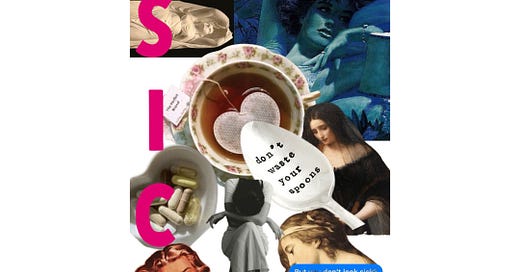

I began 2024 sick—not with any of the “big 3” (Covid, Flu, RSV), but with a special secret fourth thing that wasn’t terrible, but wasn’t great either. I haven’t been sick with much of anything since pre-pandemic, because masks and vaccines work (and I never stopped masking in public spaces). So, getting sick a week ago felt uncomfortable and unfamiliar. As someone who has never been “good” at being sick, this has felt especially difficult. I’ve been chugging along, though—sitting with my feelings, and doing the time.

I’ve written about this in so many spaces previously, but I was put on Zoloft at 17 after experiencing bullying from my friends, and also because I started to subconsciously track every sensation I felt in my body. This tracking came on after I got really sick with stomach issues. Once I got better, I still tracked my sensations and I could barely function. Medication and therapy were the only two things offered to me at the time. The Zoloft numbed me out beautifully, which, at the time, was a welcomed feeling. But I spent the next decade further separated from my body, from its sensations, from feeling. Only in the last few years have I begun to feel more, and in this feeling more, I have felt more distressed. There is always the option to increase my meds, but for now, I am trying other things. In my experience, running from the feeling makes the feeling feel heavier, scarier, darker. I am now trying to lean into whatever sensation arises—especially sensations that I dislike.

Recently, I re-read the infamous essay, Sick Woman Theory (2016) by Johanna Hedva. I was cleaning out all of the screenshots on my phone (as one does) and came across one I took of an excerpt from their essay (as quoted in a gorgeous piece by

). I don’t remember when I first read Hedva’s essay, but I think it’s fair to say that I wasn’t yet in a place to understand it. I wasn’t yet in a place where I needed it.Hedva defines Sick Woman Theory as:

…an insistence that most modes of political protest are internalized, lived, embodied, suffering, and therefore invisible. Sick Woman Theory redefines existence in a body as something that is primarily and always vulnerable… Sick Woman Theory claims that it is the world itself that is making and keeping us sick.

Hedva is clear that though “woman” is in the title, the term is meant to be inclusive. Hedva, themselves, is a queer disabled person of color. They note:

The Sick Woman is an identity and body that can belong to anyone denied the privileged existence—or the cruelly optimistic promise of such an existence—of the white, straight, healthy, neurotypical, upper and middle-class, cis- and able-bodied man who makes his home in a wealthy country, has never not had health insurance, and whose importance to society is everywhere recognized and made explicit by that society; whose importance and care dominates that society, at the expense of everyone else.

The screenshot I had taken many months ago was this part:

Sometimes a question shoots through me: Are there people who don’t have to think about their bodies? It makes me wonder what conditions, what supports, have conspired in the world to make this true for them. Why is it not true for someone like me?

I can vaguely remember a time when I didn’t think about my body, but it feels so long ago, so untouchable. It was some time before I was four, before I had the experience of several urinary tract infections; before I ever knew my body could be a site of pain. I have been a person who thinks about their body—sometimes obsessively—since then. It makes sense that I would think even more about it as I age, I suppose. But I also know it’s not just that.

I appreciate that Hedva brings up how another language (Cree) situates illness:

In Cree, one does not say, “I am sick.” Instead, one says, “The sickness has come to me.” This feels like a more productive understanding of illness because it respects both the self and the illness as separate entities that can interact and encounter each other, rather than one subsuming the other.

What has come to me so far in this life is the following: neurodivergent; chronic mental health issues (pmdd, anxiety, panic disorder, pstd); learning disabilities; genital herpes that forever lives in my body awaiting to erupt; and general body pain as I age.

I have a body that has endured childhood emotional neglect, medical trauma, and multiple sexual assaults. I live in a country that expects and takes so much without dispensing care.

Lately, I have been feeling very “why me?” Why must I feel everything? Why must everything I feel distress me? Why can’t I be like other people? Why, why, why?! I hate myself in these moments. My brain attempts to course correct by making myself feel even worse by thinking, “I don’t have it as bad as some people. I shouldn’t complain.” While that might be true, it’s never a particularly helpful thought exercise. I wrestle with my own internalized ableism. I wrestle with the fear of becoming more disabled than I already am. I so badly want to control any and everything, knowing full well that I can’t.

We don’t all start out in this world on a level playing field. We don’t all end up that way either.

I also know that the disabilities I have gained in adulthood have allowed me to be more expansive in both mind and body; in vulnerability; in compassion; in empathy. These disabilities and illnesses that have come to me have, in some way, helped me in subverting the status quo.

Disabled folks know the most about care—we have to since it’s so infrequently offered in our mainstream, ableist culture. In their essay, Hedva says about care and protest:

The most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself. To take on the historically feminized and therefore invisible practice of nursing, nurturing, caring. To take seriously each other’s vulnerability and fragility and precarity, and to support it, honor it, empower it. To protect each other, to enact and practice a community of support. A radical kinship, an interdependent sociality, a politics of care.

This is the world I dream of: where people give a shit about each other even if they don’t know each other. It sounds so simplistic, and yet, we continue to see during the Covid pandemic that most people can’t even muster that. It doesn’t help that here in the U.S. we have a collapsing healthcare system that doesn’t care whether you’re in pain or not; whether you’re ill or not; or whether you live or die, especially if you’re disabled.

As so many disability activists have reminded us: we are all moments away from becoming disabled (or further disabled) ourselves. Ableism lets you think this will never happen to you, thus, you don’t need to care. In her essay from 2022 titled, You Are Not Entitled To Our Deaths: COVID, Abled Supremacy & Interdependence, Mia Mingus writes:

Abled supremacy means that many of you mistakenly think that if you do get COVID and if you end up with long COVID, that the state will take care of you or that your community will. You believe this because you do not know about the lived reality of disability in this country… Our government does not care about the disabled people that already exist. So, if you think it will care for you if you become disabled from COVID, as millions more will, then that is a function of your ableist ignorance.

The state doesn’t care about you now. They certainly won’t care about you when you become disabled. Doesn’t that infuriate you? Doesn’t that scare you? It should. You should also want better for those who have had to put up with the state’s violence for decades with no change.

As disabled people, we are used to this, which is why disabled community care has been a forever collective action and has often superseded waiting around for the state’s response.

I want to live in a world where everyone gets what they need (and then some). I want to live in a world that doesn’t throw people away. I want to live in a world where nobody has to worry about going to work (ever) especially when they are sick or having a flare. I want to live in a world that loves people over profits and invests in its bright kaleidoscopic communities.

Maybe we’ll get there when more people become disabled.

As Hedva writes:

…once we are all ill and confined to the bed, sharing our stories of therapies and comforts, forming support groups, bearing witness to each other’s tales of trauma, prioritizing the care and love of our sick, pained, expensive, sensitive, fantastic bodies, and there is no one left to go to work, perhaps then, finally, capitalism will screech to its much needed, long-overdue, and motherfucking glorious halt.

Our sick, disabled, and “fantastic bodies” will break capitalism.

Who Actually Talks About Student Loans—And How -

Can “Rubenesque” Be Feminist? - Olivia McEwan

The Work of Women of Color Academic Librarians in Higher Education: Perspectives on Emotional and Invisible Labor - Tamara Rhodes, Naomi Bishop, & Alanna Aiko Moore

A song per te:

There's something deeply wrong with a state that doesn't give a shit about us. Isn't that why we have states in the first place? To make sure that we all have our needs met?

Listening to this feels like the most seen I've ever felt -- I've ever been. From beginning to end: absolutely incredible. I didn't even know if this was a series of feelings that others feel/felt/are always feeling, too (but isn't that another ableist trick: making you think that the most "radical" thoughts are just delusions, you're just sick?), but to hear that there's a name to describe this line of thinking, that others feel it too... thank you so much for sharing your story and these ideas. Incredible, inspiring work!!!